THE EMERGENCE OF ENTREPRENEURIAL MAFIAS AND ILLEGAL MARKETS

The fight against organised crime, in the European Union but also elsewhere, somewhat resembles the fight between a fox and a lion, where the fox’s cunning and agility often triumph over the lion’s strength.

In recent decades, the growth of organised crime in Europe has followed that of the main illegal markets, and has taken advantage of both the opportunities offered by the contraction of time and space brought by globalisation, and the unification and enlargement process of the European Union. Small local illegal markets have expanded into national markets, and then have become part of an international system, and in a reverse process, global illegal market forces have broken through local barriers in a revolution from above and outside, promoting instability and conflict in various regions on Europe’s borders and even within Europe.

Until the early 1990s, this process developed along fairly similar lines in different parts of Europe. It was led by ‘hardened’ criminal gangs, highly visible and violent, intent on territorial control, very protective of their own independence and identity compared with other components of the criminal universe such as terrorism and economic crime.

The markets and mafias that led this expansion were those involved with drugs produced in areas outside Europe and distributed in the two key markets of Western Europe and the United States. Between the 1950s and the 1990s, prices, consumers and sales of heroin, cocaine and cannabis increased everywhere in the West.

The main beneficiaries of this expansion were criminal gangs in Italy, the Balkans, the Middle East and Latin America, as well as the eternal old Chinese mafia.

These criminal groups rapidly moved from extortion, racketeering and smuggling on a local scale to international production and trade in drugs. Their use of corrupt political connections in their countries of origin combined with their immersion in ethnic diasporas and the vast communities of immigrants living in the places where the drugs are distributed protected them from police investigations and gave them privileged channels for laundering the profits.

In some areas like southern Italy, the conquest of vast territorial enclaves on the back of the growth in drug profits meant for the dominant mafias there the possibility of expanding into legal markets, constituting deadly competition to lawful enterprises and appropriating a significant share of the national and European funds destined for the development of depressed areas.

In other areas with a more cosmopolitan commercial tradition, the drug mafias also appeared in the contiguous arms and human trafficking markets, though without moving their main focus, until the 1990s, from the most lucrative sector – drugs. These same criminal gangs linked up in some cases with nationalist and separatist terrorist movements, though always on the basis of ad hoc agreements and a clear division of roles and responsibilities. The classic example of this is the collaboration of Turkish nationalist terrorist groups and Turkish drug cartels in organising the assassination attempt on the Pope in 1981.

The threat or use of physical violence has been a cornerstone of the activity of these criminal groups in illegal internal and global markets. The mafia wars in Italy in the 1960s and 1980s, in the Balkans during the breakdown of Yugoslavia, in Colombia and Bolivia in the 1970s and 1980s, and in South-East Asia during the period of dominion of the Golden Triangle, the opium protection zone, were fought by families, and illegal cartels and federations with territorial sovereignty, means of coercion and techniques often not entirely dissimilar to those of States.

The use of violence was also a last resort and a guarantee of respect for contracts when it came to criminal cartels on the one hand and financial crime on the other. This form of serious crime has also grown as the mafias have grown, but away from the spotlight of the media and public authorities, interested in the problem only when banks fail or bankers meet a tragic end.

THE EUROPEAN RESPONSE

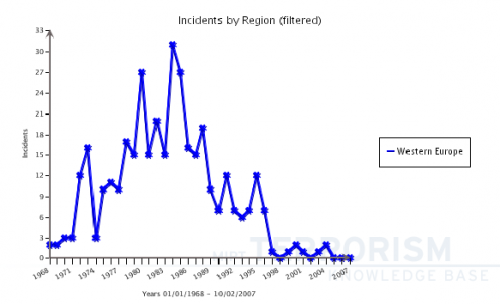

The legislative, political and judicial response of individual European countries to the challenge of new types of criminality came late, between the late 1980s and early 1990s. Until the 1980s, when the illegal markets were expanding at their fastest rate, the attention of public opinion and European governments was turned to terrorism. Terrorist activity had had Europe as its main theatre of operations for the entire twenty-year period from 1970 to 1990. As shown by the table below based on the Rand Corporation database which has recorded all terrorist acts from 1968 to the present day, of all the world’s regions Europe was the worst affected. Out of 5 433 attacks worldwide between 1970 and 1989, 1837, or 33.8%, took place on European soil, compared with 1 232 in Latin America, 1 200 in the Middle East, and only 388, or 7.1%, in North America.

INTERNATIONAL TERRORIST ATTACKS FROM 1970 to 1989

| REGION | Incidents | % |

| Western Europe | 1,837 | 33.8 |

| Latin America, Caribbean | 1,232 | 22.7 |

| Middle East, Persian Gulf | 1,200 | 22.1 |

| North America | 388 | 7.1 |

| Africa | 334 | 6.2 |

| South Asia | 205 | 3.8 |

| Southeast Asia, Oceania | 149 | 2.7 |

| East, Central Asia | 66 | 1.2 |

| Eastern Europe | 22 | 0.4 |

| TOTAL | 5,433 | 100 |

|---|

Source: RAND MIPT Database.

An increase in the fear of terrorism in Europe left its mark on the 1970s and 1980s, and closely followed the graph of attacks. This reached its peak, as the figure below shows, in 1985-86, and then fell rapidly until today.

From then on, there has been a rapid reduction in attacks in Europe, but almost nobody has realised that in the meantime organised crime has become deeply rooted, exploiting the polarisation of collective alarm about the terrorist threat.

Until the early 1990s, Italy was the only country in Europe where the problem of organised crime was at the centre of the public’s attention. Already by 1982, when General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa was assassinated in Palermo, Italy had begun to overhaul its anti-mafia legislation, making the need to attack the economic and entrepreneurial side of major crime central to its efforts by abolishing banking secrecy for judicial investigations, seizing the proceeds from crime and setting up specialised, centralised anti-mafia police units.

INTERNATIONAL TERRORIST ATTACKS IN EUROPE

1968-2007

Source: RAND MIPT Database. Attacks in which at least one person died.

The spread to other European countries of concerns about the threat of crime, as well the creation of the first instruments to combat it as a common threat, is one of the great merits of the European Union and the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht. Although the Treaty did not yet explicitly identify organised crime as a serious threat or as a central component of the ‘third pillar’ of the Union – this was something the 1997 Treaty of Amsterdam did – it did propose the establishment of Europol and opened the way for the EU to lead the fight against organised crime.

The European Union in some ways stole a march on its own Member States in identifying the new threat. Since then, European policy on this issue has been constantly evolving. Between 1998 and 1999, an action plan was drawn up, and in Tampere, Finland, an overall strategy was approved that provided for joint investigative teams for the EU Member States, the creation of a task force of police chiefs, the birth of Eurojust to coordinate national prosecuting authorities, and a stepping up of the fight against money laundering and the action of the financial intelligence units.

In 2001, on the back of reactions to 11 September, one of the most powerful measures in the fight against all types of cross-border crime was approved: the European arrest warrant. This legislation created a de facto European judicial area by eliminating in one stroke the cumbersome judicial reciprocity procedures that slowed down the activities of prosecution services in the EU Member States.

Finally, the draft European Constitution provided for the creation of a proper European Public Prosecutor and further strengthened Europol.

Alongside the intergovernmental activities of the EU’s executive bodies came the signature of three new Council of Europe Conventions – on trafficking in human beings, money laundering and terrorism – and the parallel adaptation of the internal legislation of individual Member States. They ended up adopting broadly similar legal standards in a number of areas such as banking secrecy, the confiscation of assets, laundering, terrorism, people trafficking and corruption. This standardisation made interjudicial cooperation much easier and further reduced the ability to evade punishment for cross-border crimes.

So there was a European response to the challenge of organised crime and illegal markets and it had an impact. It was not the deadly blow dealt by an old lion irritated by the provocations of a fox, but nor was it an impotent roar. Furthermore, these measures were enhanced and made universal by the UN Convention on Transnational Organized Crime, which was signed in Palermo in 2000 by 125 countries and entered into force in 2003.

The most significant consequence of the set of measures against organised crime and money laundering adopted by the European Union and its Member States since 1992 has probably been that it has led to a reduction in the use of physical violence by criminal groups for settling disputes and attacking the biggest threats to their power.

Quicker exchanges of information, better international coordination of investigations, and more effective legal and technical instruments available to the police and prosecution services have meant that the number of perpetrators of mafia murders, massacres and kidnappings evading capture has dramatically fallen in almost all European countries. In the European mafia and anti-mafia capital Palermo, killings linked to organised crime have almost been eliminated, falling from 100 to 150 per year 15 years ago to 2, 3 or even none at all more recently. Even in some of the turbulent areas on the edge of the EU, such as Albania, Serbia, Turkey and Russia, the use of violence and massacre as a method of settling criminal disputes has become rarer.

In other words, the same process that occurred in the United States between the 1920s and the 1970s, limiting the use of the most extreme forms of coercion by professional criminals, has taken place in Europe and some other parts of the world. In the American mafia capital Chicago, mafia homicides fell from 599 in the 1920s to 61 in the 1960s to a negligible figure today.

The drop in criminal violence in Europe during the 1990s not only concerned the mafia and the principal illegal markets, but was also more general. Both the data for crimes reported to the police and the victimisation surveys promoted by the EU itself show a decline between 1992 and 2005 by more than 30% for the whole of Europe and as much as 40% in some individual Member States.

Alongside the response of the European public authorities to the threat of crime there are also sociological, demographic and economic causes that help to explain this phenomenon, which require more detailed investigation. Here it is sufficient to point out how the use of violence as a strategic resource by organised criminal gangs has fallen significantly in today’s Europe.

THE NEW LANDSCAPE

Such a marked reduction in the figures for violence cannot be attributed solely to the response of the European public authorities to organised crime. The drop in violence has also occurred in places where these policies have not been enforced, or where they have had only an indirect effect.

The phenomenon should also be interpreted as the start of a response by major organised criminals to the more effective measures to combat crime, in line with the rules of the continuing game between the fox and the lion.

This response is a strategy partly dictated by circumstances and partly born out of a reasoned choice. It is in the process of establishing a new landscape in which three factors are at work.

The first is a change of structure. Criminals are switching from hierarchies and criminal gangs to more fluid and complex structures where the ‘network’ is becoming more important as the predominant form of organisation. Today’s international criminal networks are very often horizontal entities without any hierarchy, central core or territorial attachment as in the past, and are characteristically very flexible with the ability to merge into vaster networks of a legitimate nature. Moreover, these criminal networks extend from the legitimate economy to the illegal economy without any break in continuity, often rendering pointless any distinction between organised crime and economic crime.

Within these criminal networks, criteria of affiliation and selection based on background do still exist, but the kind of total commitment demanded by secret societies such as the Triads and the Sicilian Cosa Nostra is no longer required. Strategic parts of the network may still have an ethnic, clan or national identity, but these are variable qualifications which do not have to be exchanged for a permanent identity.

The second factor is the diversification of the areas in which criminal groups are active, a response to a number of long-term trends in the illegal economy. The most important of these trends is the decline in the scale and centrality of the drugs market in the overall panorama of crime.

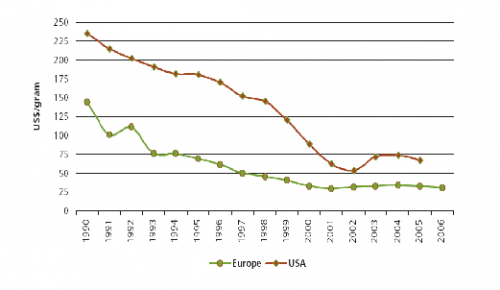

Almost nobody, not even the experts, predicted the change that has occurred in heroin and cocaine prices in the wealthiest markets – Western Europe and the United States – since the 1990s.

Yet there has been a steady decline in retail and wholesale prices each year, which has been uniform across all the countries of Western Europe and in the United States. One gram of heroin used to have an average street value of 196 euros in 1990 in the 18 Western European countries. The price had tumbled to 56 euros by 2006. However, the important price for the drugs mafias is the wholesale price. Over the same period, this price has fallen from 106 to 25 euros. In the United States, this tumble has been even more pronounced.

Because the number of European and American consumers has remained constant or diminished over the same period, the turnover of the largest illegal market has now shrunk to less than a quarter of what it was. With it, the profits of the assorted people involved in the drugs trade, and of the international organised criminals who control wholesale sales, have also shrunk. The price trend for cocaine has been similar, with the increase in the number of consumers in some European countries since 2000 being offset by a vast reduction in the number in the United States.

If we add to the drop in prices the parallel increase in operating risks signified by the increase in the number of arrests and particularly of drug seizures – these have doubled for heroin, and for cocaine have reached nearly 50% of the goods supplied – we can understand why the drive to find new markets has become so important for drug dealers.

The shrinking of the drugs market was therefore accompanied – also in the 1990s – by growth in trafficking in human beings and the smuggling of small arms and counterfeit goods.

AVERAGE RETAIL AND WHOLESALE PRICES FOR A GRAM OF HEROIN IN 18 EUROPEAN COUNTRIES AND THE USA FROM 1990 TO 2006

UNODC data for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Iceland, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and Ireland.

Some of these new areas of international organised criminal activity are not dominated by the criminal networks, being instead populated by an assortment of different types of people, but their scale and profitability are in many cases capable of making up for the drop in drug profits.

The third factor in this new landscape is the fusion of criminal networks with those of ‘conflict traders’ in the world’s danger zones. Wars are increasingly becoming organised criminal enterprises, and these enterprises are becoming increasingly interested in wars. Wars, like the mafias of the past, have become a way of life, systems for generating profit, exercising political power and giving employment to young people barred from the normal routes to education and employment.

The people fighting these conflicts are increasingly difficult to distinguish from criminal bosses. They are venture capitalists who care little about country or identity and a lot about business and the spoils of war. Anyone with even a passing knowledge of the situation in places like Afghanistan, Kosovo, Liberia, Congo, Sierra Leone and other similar countries can appreciate how easily the concept of criminal wars applies rather than the traditional approach of international relations.

NEW STRATEGIES

This new landscape demands that Europe’s strategies for dealing with large-scale crime be brought up to date. First of all, we need to speed up the process of improving operational aspects of Europol and Eurojust and of establishing the European Public Prosecutor. National police forces and European judicial police bodies must also be given the flexibility and intelligence capability required for them to identify criminal networks, which are much more elusive than clans or cartels.

Then there is the issue of curbing criminal wars by recognising them as a subject of relevance to both the EU’s internal security policy and its foreign policy. The fusion of some parts of the second and third pillars of the European Union is extremely urgent. The criminal dimension of many civil wars, ethnic conflicts and secessionist and separatist offensives taking place in Africa and Asia, in which Europe is involved through its rapid intervention and peacekeeping forces, must be properly recognised so that foreign policy positions can be taken that take better account of reality and are more effective.

Pino Arlacchi

Non sono una persona complicata. La mia vita pubblica ruota intorno a due cose: il tentativo di capire ciò che mi circonda, da sociologo, e il tentativo di costruire un mondo più decente, da intellettuale e militante politico.

Non sono una persona complicata. La mia vita pubblica ruota intorno a due cose: il tentativo di capire ciò che mi circonda, da sociologo, e il tentativo di costruire un mondo più decente, da intellettuale e militante politico.